They are a close, extended family of sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles. They share vacations and holidays, burdens and joys. But they also have an expansive history of cancer: one sister had uterine cancer, and an aunt and cousin each had breast cancer, just within the past year.

Yet some members say they feel "lucky." They were screened for a damaged gene - a mutated BRCA2 - and though more than half tested positive, the screening found two cancers in very early stages, giving the women excellent prognoses without having to endure grueling chemotherapy or radiation treatment.

"Despite the fact that we have this gene - I feel so lucky," Ellen Kelly, 64, said. "I would have never known I had uterine cancer if I didn't go through the screenings and get tested. And this type of cancer doesn't usually cause symptoms until it's advanced so this testing saved my life."

The family's saga began with a phone call from their cousin, Nancy O'Sullivan, to Ellen. Nancy had breast cancer, had tested positive for the damaged BRCA2 gene and thought her cousins should consider getting tested. Ellen's grandmother died of ovarian cancer and her mother had breast cancer early in her life but both died before testing was available. Cancer had infiltrated the family tree and Ellen had an aching suspicion genetics were playing a major role.

Ellen shared Nancy's warning with her relatives. But making the decision to be tested was agonizing, sending the family, originally from the Bronx and now scattered across North Jersey, Rockland and Westchester counties, into a tailspin. They each received a family medical history and then promptly stuffed it into far-flung nooks in their homes, didn't talk about it, tried to ignore it.

"I didn't want any part of this - I didn't want to be tested, I didn't want to know if I had the bad gene," said Diane Gannon, who is Ellen's sister and works for human resources at Holy Name Medical Center. "I felt like it would be the beginning of the end if it was positive - that it would be a death sentence."

Julie Canavatchel, Ellen's daughter, quietly folded the document and put it into a little-used desk drawer, removing it from her sight and her mind. She went about her life as a single mom, working in a local school and taking care of her 12- and 9-year old boys.

"It was the fall and I was really busy with the boys and their activities," Julie said. "I also knew I didn't have to do anything unless my mom decided to get tested and then came back positive, so I forgot about it."

But deep down, they all knew this wasn't something they could ignore. Screening could potentially save their lives and ultimately, 11 members agreed to it. Six came back positive, triggering a collective sigh of relief or wave of anguish with each test result.

Perhaps the most difficult outcomes were those of the youngest family members. Two tested negative, but one, Julie, was positive. The gene had been passed down to the next generation.

"We were really hoping this damaged gene was ending with us and our children wouldn't have to deal with it," Diane said as her eyes filled with tears. "We do have days when we wonder if this will ever end."

Despite the results, they are all gratified they were tested.

"As bad as it was to find out, at least you could do something about it," Ellen said. "If we didn't get tested, we would always be thinking about it in the back of our minds."

But in some cases, hearing the results was just ghastly. Ellen, who tested positive and was found to have uterine cancer in subsequent screenings, was being wheeled into surgery when Julie got the call from the genetic counselor saying that she was positive.

"That was just horrible," Julie, 42, said. "My mom was going in for surgery for uterine cancer and we were all there - everyone was crying. Now that it's all over, I'm glad we did it but it was scary."

Pat Butler, Ellen and Diane's aunt, was more open to getting screened. The fear of cancer always nagged in the back of her mind - her mother, who was Diane and Ellen's grandmother, died of ovarian cancer, her sister and an aunt each had breast cancer.

"Since the time I was little I always worried about getting ovarian cancer," Pat, 68, said.

Meantime, Pat also learned that Medicare would only cover mammograms every other year instead of annually and considered skipping the screening this year. But the BRCA2 gene testing changed her mind.

"Once I found out I was positive I was really careful about getting my mammograms," Pat said. "In May, I found out I had breast cancer. If I didn't get tested, I might have skipped it this year."

Damaged BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes don't do their job of helping to suppress tumor growth so cells are able to multiply rapidly. Women with a mutated BRCA2 gene have about a 45 percent chance of developing breast cancer compared to 12 percent in the general population. It increases the risk of ovarian cancer between 11 and 17 percent, compared to 1.4 percent on average.

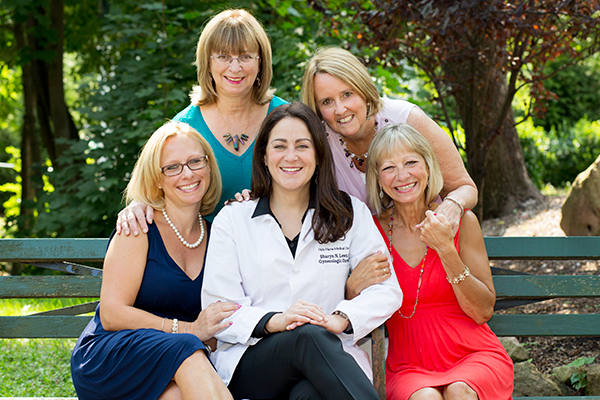

To prevent getting ovarian cancer, the four women spanning three generations - Pat, Ellen, Diane, and Julie - opted for surgery to remove their ovaries and fallopian tubes. They clung close and helped each other through the procedures, physically and emotionally.

"We've always been close but now we've lived through this and shared something so important, it's made us even closer," Diane said. "We joke that this is what our mom and grandmother had to leave us - a damaged gene. They couldn't leave us a million dollars?"

In addition to the unwavering support they've given each other, all four women credit Dr. Sharyn Lewin with potentially saving their lives. Dr. Lewin, Holy Name Medical Center's medical director of gynecologic oncology who performed all four surgeries, allayed their fears prior to the procedures and made herself available to them days, nights, and weekends after they went home.

"Dr. Lewin is absolutely a doll," Pat said. "Besides being a good surgeon she assured me that everything was going to be all right and calmed me down. She made me feel like I was part of her family."

Diane, who suffered an adverse reaction to medication after the procedure and was sidelined for weeks longer than expected, said she's still glad she had the surgery.

"I worried I wouldn't be whole again, wouldn't feel like a complete woman," Diane said. "But now I'm so grateful and look at it like it saved our lives. Before the surgery, I felt like a ticking time bomb. Now I feel like a whole woman and I can say I'm cancer free."

Learn more about Gannon Family gynecologic oncology doctor today